WHAT IS HERALDRY?

There is more to heraldry than people think. It’s not just to do with coats of arms, though that is an important part of it. Heraldry, broadly speaking, covers the activities of the heralds. Historically, the heralds were the messengers of the king. In the past, the role of the king was primarily concerned, in one way or another, with warfare – be that expansive or defensive. Traditionally, history has remembered kings as being either good or bad based on their abilities as a warlord. For example, Henry III, who enjoyed one of the longest reigns in English History 1216-72), has been remembered as a bad king because his interests lay more in the field of art and architecture – It is to Henry that we owe the building of Westminster Abbey to Henry. However, he did not excel in the field of battle, and has therefore been remembered as a weaker king than say, Richard I (the Lionheart) who’s military prowess is legendary. Equally, it was not enough to wage war; you had to be good at it. King John I for example was a warmonger, but an unsuccessful one – and has similarly been remembered by history as a bad king.

In a time when success on the battlefield was vital to the monarchy, a good communications network was integral. Today we use the most up-to-date technology to ensure a strong network of communication; during the medieval period the king relied on his heralds to receive and deliver messages. A medieval king did not have a standing army. Instead kings relied on their barons who would muster an army for the king out of the people they lorded over. Like today, battle during the medieval period was chaotic – it was hard to know who was on which side. A system developed which meant that knights would wear badges on their armour so they could be recognised. Both the Crusades and tournaments assisted the formation of heraldic code. During the Crusades a great number of people travelled to the Near East from all over Europe and subsequently, it has been argued, this led to a more formalised means of identifying important individuals. Similarly, the chaos of tournaments meant that it was often difficult to identify the participants. As medieval tournaments developed over time, and became bigger and grander events, heralds were called upon to take note of the various coats of arms of the different knights. It was the job of the heralds to make sure than no two coat of arms were the same.

WHO ARE THE HERALDS?

The heralds were, and still are today, part of the royal household and under the command of the Earl Marshall of England who is traditionally the Lord of Norfolk. There are thirteen heralds in total and are still payed by the Queen. From 1420 the heralds had a common seal, and in 1484 Richard III granted them a charter of incorporation and they were given a building in Cold Harbour in Upper Thames Street which became known as the College of Arms. The site was moved during the reign of Queen Mary I and remains in the same location today on Queen Victoria Street near the St Paul’s Cathedral. The College of Arms functions as the place where the heralds work, where heraldic records dating back to the middle ages are kept, and was the traditional setting for the Court of Chivalry which would settle any dispute over arms and bring those to account who did not observe the rules of chivalry.

THE ROLES OF THE HERALDS

Today the heralds organise and manage state ceremonies such as coronations, funerals, and the opening of parliament. They advise on matters of government which relate to peerage, honours, and ceremonials – making sure that everything is done properly in accordance with tradition. They assign military badges, not for uniforms, but for ships and airplanes etc. Heralds also maintain a register of arms, grant coats of arms, and undertake private commissions for members of the public: working on matters of genealogy and peerage.

THE GRANTING OF ARMS

Any ‘notable’ person can be granted arms. Today, notable refers to anyone deemed to be a ‘pillar of society’: someone who makes a contribution to the community; a member of a charity or the council; a person who has a university degree, etc. However, even if on paper an individual fits the bill, the heralds after commencing their research maintain the right to withhold the receiving arms. Historically, as they did not go into battle, women did not have the right to their own coat of arms and would take on that of their father or husband. Since being allowed into the armed forces this has changed– for example, since being made a Dame, Esther Rantzen commissioned her own coat of arms in February 2015. Members of the Clergy, although they did not partake in battle, were entitled to their own coat of arms as they were often on the front line of the battlefield supporting the troops. Instead of a helm, the appropriate ecclesiastical headgear would be depicted, e.g. a bishop would have a mitre on their coat of arms.

APPLYING FOR A COAT OF ARMS

Applying for a coat of arms is not simple. The Officer of the College of Arms must be contacted who will invite the applicant in for a talk. After a discussion, if the individual or company decides to go ahead, the heralds will do the required research to determine if the applicant is eligible for a coat of arms. If found eligible, the Earl Marshall will be contacted on the candidates behalf, and if the Earl Marshall approves, he will issue his warrant to the appropriate King of Arms and the process will begin. Scotland is unique within the United Kingdom in that it has its own system regarding the issue of a coat of arms. When the system was created, Scotland was a separate country and today maintains its established heraldic system. It is not, however, just British citizens who can apply for a coat of arms, as the Queen is the head of the Commonwealth, anyone within the commonwealth is eligible to apply.

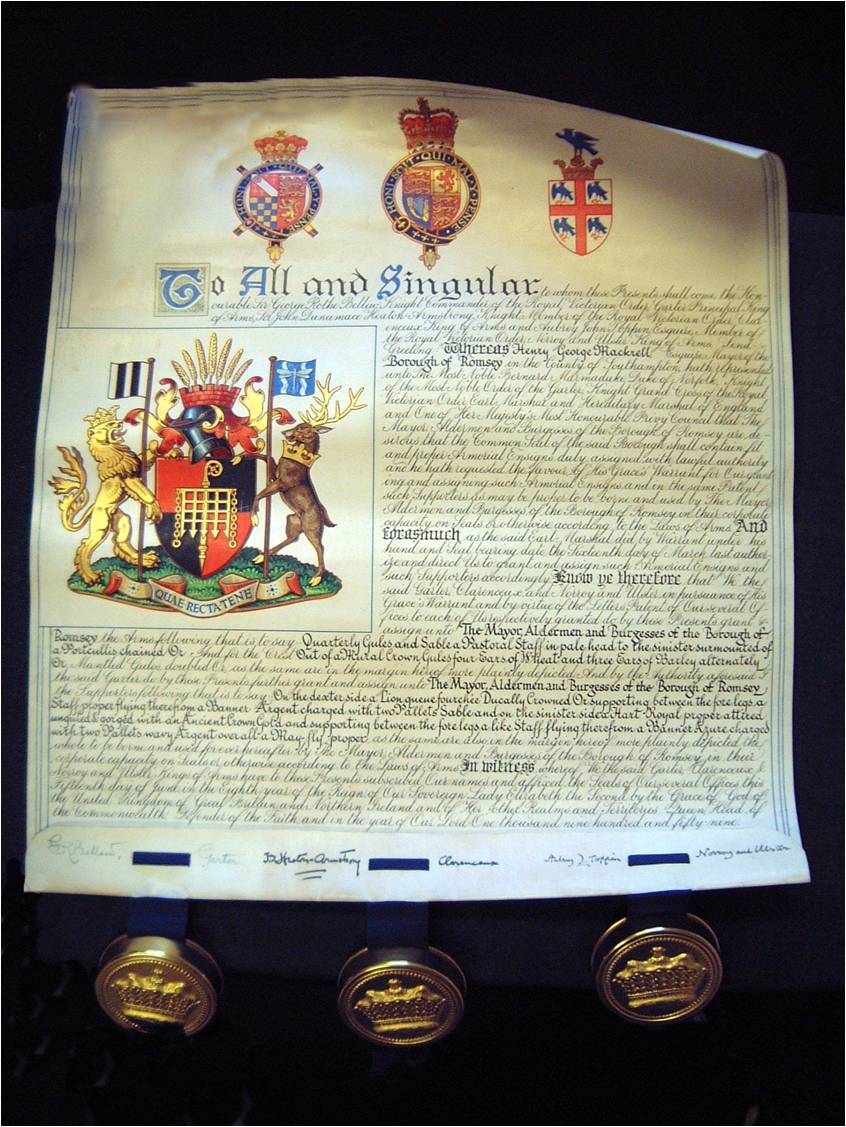

ROMSEY

Romsey received its official patent in 1959, and possibly the most recognisable feature of the coat of arms is the portcullis. The official heraldic language is Lesen and is the language which was used to write the Letters Patent which described the coat of arms afforded to Romsey. The badge coat of arms is split into ‘quarterly gules and sable’ meaning quartered with two red squares and two black. There is a ‘pastoral staff in pale head to the sinister surmounted of a portcullis chained or’ – meaning that the pastoral staff is facing ‘sinister’ (Latin for left – the bearers left) and is placed on top, and down the middle, of the ‘or’ (meaning ‘gold’) portcullis. On the top of the badge is a red mural crown in the shape of a brick wall with four ears of wheat, and three ears of barley alternately. Supporters (symbols on each side of the badge) are only present on the arms of a lord or a company. Romsey’s coat of arms has two supporters. To the dexter (right) is a lion with its tail forked wearing a ducal crown. The Lion is flying the banner of Lord Mountbatten who helped commission the coat of arms. On the sinister is a heart with a crown around its neck. The Hart is holding a blue and white flag with a mayfly on it, which represents the River Test. The motto ‘quae recta tene’ was added below the shield which means ‘hold fast that which is right’. Despite adding a motto, they are informal and anything can be added.

Coats of arms use a mixture of colours, materials and shapes. Metals and furs are used, five tinctures (colours) and numerous geometric shapes. As mentioned above, a motto is not a mandatory element of a coat of arms, nor an official one. Names are not hereditary, so for example – sadly – having the name Windsor does not entitle a person to use the coat of arms of Windsor. For further information on heraldry there are a number of starter and advanced works available, some of which are listed below.

An Alphabetical Dictionary of Coats of Arms belonging to Families in Great Britain and Ireland, forming an extensive Ordinary of British Armorials upon an entirely new plan [‘Ordinaries’], by, John Woody Papworth

Basic Heraldry, by Stephen Friar & John Ferguson

Complete Guide to Heraldry, by A.C. Fox Davis

The Dictionary of British Arms

The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales; Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time, by Sir Bernard Burke